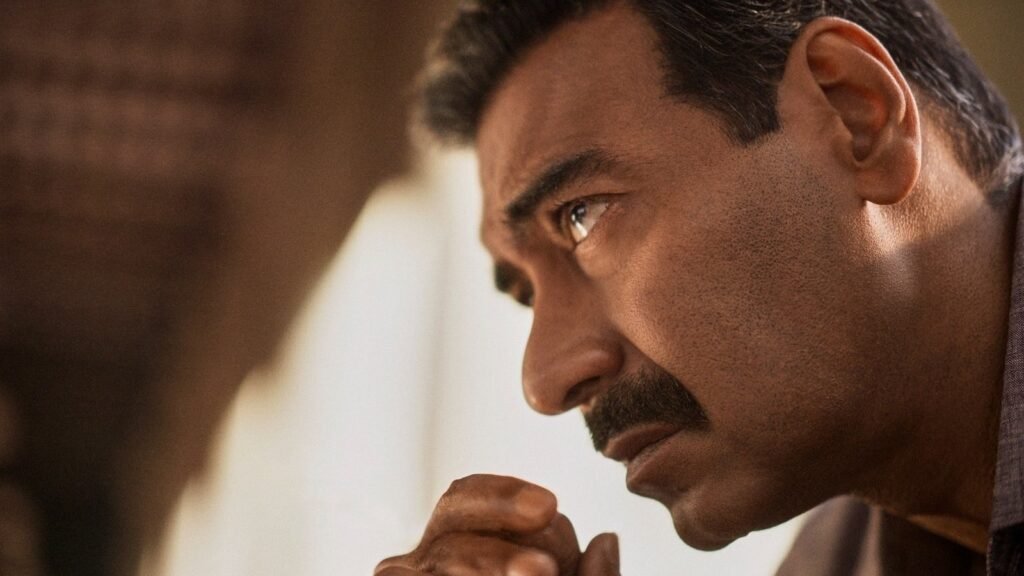

Maidaan Review: In 2019, work on a film began. A sports biopic, that was this. which discusses football, the national sport that is least watched. The tale of the man who oversaw the Indian national football team’s coaching staff. Under his training, the team made waves all over the world and Won gold medals from the Olympics to the Asian Games.

Consequently, the years 1950–1960 are referred to be the “golden period” of Indian football history. Syed Abdul Rahim was the name of the charming gentleman. “Maidaan” is the title of the movie that was made about him. This took five years to complete and is now available in theatres.

| Movie | Maidaan |

| Director | Amit Sharma |

| Writers | Saiwyn Quadras, Aman Rai, Atul Shahi, Ritesh Shah, Siddhant Mago, Amit Sharma |

| Cast | Ajay Devgn, Priyamani, Gajraj Rao, Rudranil Ghosh, Chaitanya Sharma, Madhur Mittal, Tejas Ravishankar, Amartya Ray |

| Duration | 181 mins |

Amit Ravindernath Sharma‘s biographical sports drama Maidaan is so real you can practically touch the blood, sweat, and tears that went into making it.

Maidaan Movie Review

It’s a story about coach Syed Abdul Rahim and his determination to build a brilliant Indian Football team and win a gold medal. The story begins in 1952, with the players suffering injuries while playing barefoot and the Indian team losing the match.

Not only does Syed ensure that the best players from throughout India are together, he also ensures that they play in quality footwear and return home with gold. He confronts his own demons and the system while doing all of this.

The film spans ten years of Syed Abdul Rahim’s life, from the infamous 10-1 “barefeet” thrashing at the hands of Yugoslavia in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, to the glories and sorrows of the 1962 Asian Games.

Some of the best sports choreography since Chak De! India’s hockey matches can be seen in it (2007). It’s evident that the movie adores football’s visual speed. It adores underdog narrative cliches. It adores the template of the period film.

But Maidaan’s downfall stems from the movie’s self-indulgence. The 181-minute ride is so full of conceited dramatisations and narrative overtakes that it can’t help but smile at its own reflection in the mirror. It ironically places the “Main” (I) in Maidaan, considering that cooperation is the ultimate objective of the sport.

It’s like watching an unending penalty shootout as a result; even the transitions are sluggish. One cannot help but draw analogies to Chak De. An unconventional coach brings together a group of youthful rookies from all over the nation. He exudes a sense of unity and emphasises the superiority of “India” over Bengal or Hyderabad. He encounters animosity and opposition from inside the system.

They shock everyone on the international scene by defying a cynical establishment. The tournament’s pattern is also well-known: India loses to the favourites in the opening game and then faces them again in the championship.

The night before the game, Rahim steps outside to touch the grass. The way the game plays out is akin to a short film, combining football intensity and war-scene camerawork to produce a compelling whole. The players are giving up their bodies and spirits instead of running and kicking.

The detail is excellent: They are engrossed in the fight to the point where they miss the final siren. They won’t let go of their opponents until they see them cease moving.

Adding Unnecessary Hurdles and Obstacles

The audience is typically duped into thinking that the thrilling source material is thrilling storytelling in most sports biopics. But it’s the big-picture overkill in Maidaan that consistently lets it down. The bloated screenplay lacks faith in the film’s underlying background. The notion of a “Golden Age of Indian football” is fraught with danger, especially in light of the nation’s past difficulties with the game.

In addition, there is the issue of a Muslim man influencing post-Partition India’s identity; in boardroom politics, bias is motivated by both culture and male ego. Rahim gets voted back in as coach at one point, and a vocal opponent even makes fun of the “democracy” of the process.

You don’t need a lot of outside obstacles or antagonists because the odds are built-in and self-explanatory. But that’s exactly what Maidaan does. Unless there’s a bomb hiding as the ball or a nuclear Armageddon, it stacks the odds so high that there is nothing left to overcome.

To begin with, Rahim’s return is defined by his lung cancer. In the last moments of the movie, there are incredibly extended images of him coughing. The man’s misery does the background score’s job; save from one touching moment (when the illness compels him to return to his family while the song “Ghar Aaya Mera Mirza” plays), it never stops.

Afterwards, there is the football federation office, where bureaucrats from Bengal load their mouths with singaras (samosas) and laugh. Its president, Rudranil Ghosh, is a hammy who puts the animated villain Dick Dastardly to shame.

In a movie that shies away from societal critique, there’s a cigar-smoking sports journalist (Gajraj Rao) whose animosity towards Rahim seems arbitrary. The rationale for this is that on their initial encounter, Rahim belittled him with a chilly retort that included a quote from Elvis Presley.

For unknown reasons, the two live-action cartoons swear to end Indian football. Even their desire to preserve Calcutta’s hegemony and eliminate Rahim’s Hyderabadi influence is misinterpreted.

Imagine if Chak De had made the federation chairman, played by Anjan Srivastava, the enemy so that his appearance in the conclusion – his appraising and reprimanding looks at the coach – would have accentuated the hero’s journey towards atonement. It’s a copout, as figures like Syed Abdul Rahim, Kabir Khan, and their skillfully assembled teams are able to celebrate their accomplishments without the need for such clumsy aids.

Selling the Handicap

To put it another way, Maidaan is always asking: Is winning really winning if it doesn’t involve a rival manager who appears to be staging a heart attack during the semifinal match instead of reacting to the game, an evil scribe and his sycophant making faces in the stands, a riot outside the stadium, and a finance ministry that is reluctant to pay for the trip?

This is an expansion of another rhetorical question: Is it really possible to understand a movie, or any other kind of art, if you don’t recognise the labour of love and sacrifice that went into making it?

This line of reasoning is related to the persecution complex that most national accomplishments have as its bookmark: If victory is not linked to victimhood, it is meaningless. This narrative also fails to stand on its own merits because it is too preoccupied with selling the handicapped.

The majority of genre clichés seem phoney because of this. “Team India Hai Hum” is an extremely uninteresting song that plays during Maidaan’s training scene. Halfway through, it appears as though the recruitment montage has been dropped.

Visual effects (VFX) and staging that reflect the artifice of a Zack Snyder universe include crowded stadiums, clouds, and foreign backdrops like Rome, Jakarta, or even Bombay’s Oval Maidan.

The rival teams are one-note stereotypes (with a particular salute to the Australian coach who almost sings out his criticisms). There’s a jarring soundtrack. A star is deserved for the wordplay, which is why the movie’s rendition of Chak De’s well-known “Sattar minute” speech centres on number one (“ek”). Between calling the games, telling the script, and mansplaining football, the Indian commentators hop around.

Finally, the performances don’t have the same impact as the legacies. Apart from the well-known personas of PK Bannerjee, Chuni Goswami, and Peter Thangaraj, the acting is restricted to the field. Although the supporting cast plays a respectable role, they are unable to rise above the noise of the entire team.

However, seniors make mistakes. Devgn’s turn is so subdued, that Rahim hardly comes across as a football coach because of how restrained his speech and body language are. He nearly vanishes into his impassivity. Other than one isolated incident in which he outclasses a standout striker, there is little background to Rahim’s love of the game or indication of his managerial prowess.

In the first half, the cigarettes appear to be forced props, and he chains and smokes like someone who knows he’s going to suffer lung cancer. The protagonist only appears alive when he’s hacking up a storm, otherwise his gloomy stare becomes a little monotonous.

Even if just because football is a powerful metaphor for life, the movie does slightly better than he does at the end. In other words, Maidaan scores during stoppage time, but it is insufficient to save the result. Wins don’t always come from an exciting conclusion. Occasionally, the difference between victory and defeat is less.